There are two key issues with regard to tax on your property dealings – identifying the:

• taxes you will have to pay

• tax deductions you can make.

Let’s take them in turn, starting with the taxes you’ll have to pay.

Stamp duty

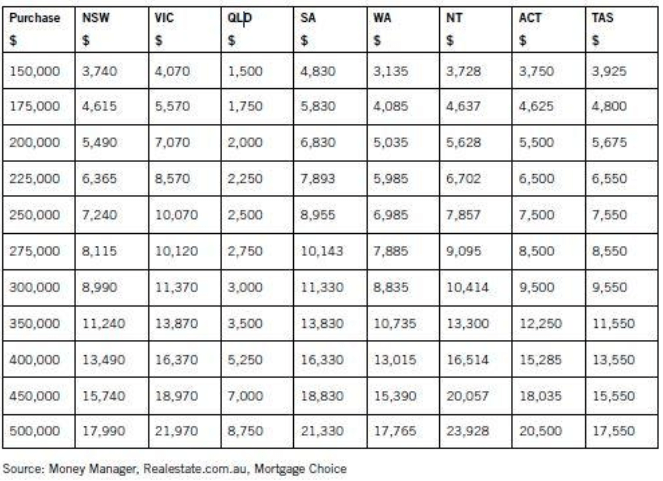

Stamp duty is a mandatory state tax on all property acquisitions. When you purchase a property in any state in Australia, a percentage of the purchase price is paid to that state’s government which is known as ‘stamp duty.’ This varies from state to state.

In some states, stamp duty is payable within 30 days of the contract going unconditional so if you have a long-term contract (that is, 60 days to six months) you may need to pay stamp duty prior to settling on the property. If the matter does not settle, you can apply to have your stamp duty refunded.

Land tax

Land tax is essentially a holding tax that we pay on investment property and in some states on principal places of residence over a certain value. It represents a percentage per annum of the value of the land we are holding. Land tax was introduced many years ago to prevent people sitting on vacant land and holding up development proceedings. The state governments at that stage established a tax to motivate landowners in emerging communities to either sell or develop. As the value of their properties rose, so did the land holding costs on a per annum basis. Unfortunately, today land tax is pretty much a state government ‘grab’ and many people who own multiple properties find their land tax bills to be $10,000s each year.

You can acquire investment property in each state with a land content up to a specified threshold (shown in the tables below) without attracting land tax in that state. Each year, the valuer general from each state government will have a valuation carried out on every property, on an unimproved basis, that is, for its land value only. (This is cited on your rates notice as your UCV or unimproved capital value.) You can query or object to these valuations. The following tables are based on the 2009–10 tax year, current at the time of publication. (The figures are updated annually by the Chief Commissioner of Taxation.) Please note, this is just a general guide so that you can budget for land tax in your feasibility studies: there are complex exemptions and calculations, so you should seek qualified tax advice on any specific plans you develop.

New South Wales

Taxable value of land | Land tax payable |

|---|---|

$0–$375,999 | Nil |

$376,000 or more $100 | + 1.6% of the amount over $376,000 |

Victoria

Total taxable value of landholdings | Land tax payable |

|---|---|

$0–$249,999 | Nil |

$250,000–$599,999 | $275 plus 0.2% of amount over $250,000 |

$600,000–$999,999 | $975 plus 0.5% of amount over $600,000 |

$1,000,000–$1,7999,999 | $2,975 plus 0.8% of amount over $1,000,000 |

$1,800,000–$2,999,999 | $9,375 plus 1.3% of amount over $1,800,000 |

$3,000,000 and over | $24,975 plus 2.25% of amount over $3,000,000 |

* The surcharge phases out for landholdings in excess of $1.8 million. For landholdings valued at or over $3 million, the surcharge is zero and the normal marginal rate applies.

Queensland

Taxable value | Rate of tax |

|---|---|

$0–$599,999 | $0 |

$0 $600,000–$999,999 | $500 plus 1 cent for each $1 over $600,000 |

$1,000,000–$2,999,999 | $4,500 plus 1.65 cents for each $1 over $1,000,000 |

$3,000,000–$4,999,999 | $37,500 plus 1.25 cents for each $1 over $3,000,000 |

$5,000,000 and over $62,500 | plus 1.75 cents for each $1 over $5,000,000 |

Western Australia

Taxable value of land | Land tax payable |

|---|---|

$0–$300,000 | nil |

$300,000–$1,000,000 | 0.09 cent for each $1 over $300,000 |

$1,000,000–$2,200,000 | $630 + 0.47 cent for each $1 over $1,000,000 |

$2,200,00–$5,500,00 | $6,270 + 1.22 cents for each $1 over $2,200,000 |

$5,500,000–$11,000,000 | $46,530 + 1.46 cents for each $1 over $5,500,000 |

11,000,000– | $126,830 + 2.16 cents for each $1 over $11,000,000 |

In addition, there is a metropolitan region improvement tax of 0.14 per cent of the unimproved value of taxable land on properties in excess of $300,000 situated in the metropolitan region only.

Australian Capital Territory

Residential properties | Marginal rate |

|---|---|

AUV* up to $75,000 | 0.6 % |

AUV from $75,000–150,000 | 0.89 % |

AUV from $150,000–275,000 | 1.15 % |

AUV of $275,001 and above | 1.4 % |

*AUV = average unimproved value (averaged over three years)

South Australia

Total taxable site value | Tax rate |

|---|---|

$0–110,000 | nil |

$110,001–$350,000 | $0.30 for every $100 or fractional part of $100 over $110,000 |

$350,001–$550,000 | $720 + $0.70 for every $100 or fractional part of $100 over $350,000 |

$550,001–$750,000 | $2,120 + $1.65 for every $100 or fractional part of $100 over $550,000 |

$750,001–$1,000,000 | $5,420 + $2.40 for every $100 or fractional part of $100 over $750,000 |

$1,000,000 and above; | $11,420 + $3.70 for every $100 or fractional part of $100 over $1,000,000 |

Tasmania

Aggregated land value | Current tax scale |

|---|---|

$0–$24,999 | nil |

$25,000–$349,999 | $50 plus 0.55% of value over $25,000 |

$350,000–$749,999 | $1,837.50 plus 2% of value over $350,000 |

$750,000 and above | $9,837.50 plus 2.5% of value over $750,000 |

Goods and services tax (GST)

Residential rent is input taxed. This basically means that a residential landlord is not required to collect GST on residential rent so the tenant doesn’t pay rent plus GST. However, as a residential landlord you will be paying GST when you incur expenses associated with the property – such as repairs and maintenance and agent’s fees. You won’t be able to claim a GST input tax credit for the GST included in these expenses. If you are personally registered for GST (your annual turnover exceeds $75,000 per annum, excluding rental income, salary and wages income) then the sale of a property will be subject to GST. Unless you’re conducting a business in your own name, or are buying and selling newly-constructed properties on a regular basis, you shouldn’t need to register for GST. On property alone, you would need to be selling more than one new property every 12 months, which as we saw in Session 5.5 is not recommended.

However, you should check your GST position with a competent accountant. I strongly recommend that you speak to an accountant who is also experienced in property trading. Make sure you budget for your level of annual turnover (and it’s best to be conservative) to work out whether you need to register for GST. If you’re registered for GST, you can claim an input credit on just about all your costs, provided they are incurred with another business registered for GST, for example, if you buy

a home from a builder or developer who includes GST in the purchase price which you can claim as an input credit. If you:

• Purchase a property from a farmer or someone not in the property business (even an owner-occupier) then GST is not included in the purchase price and therefore there is no input credit to claim

• Are renovating property or spending money on consulting fees or various applications, then you will be charged GST and you will need to keep a record of that for lodging with your Business Activity Statement (BAS).

If you’re a passive investor, you shouldn’t need to concern yourself with GST. For investors who are just buying odd properties here and there – perhaps renovating them and on-selling from time-to-time – you may not be active enough to register for GST. Again, get a competent accountant to advise you.

Capital gains tax (CGT)

When you sell (or otherwise dispose of) an asset acquired after 19 September 1985, you are liable for capital gains tax (CGT) on any increased value or profit. In terms of property, your home is exempt but your investment property isn’t. The amount of CGT is calculated as the sale price (consideration) minus the acquisition cost of the property (reduced by 50 per cent where the property has been held for a period of 12 months or more which our structure strongly recommends).

Calculating CGT is a complex business (particularly since, for a property purchased prior to 21 September 1999, you have the option to index the acquisition cost for inflation). Don’t panic! Most people don’t do their own CGT calculations. They keep their basic purchase/expenditure/sale records and hand them over to a competent accountant. Highly recommended.

CGT is calculated at 50 per cent of the profit. Basically, half the profit will be tax-free and the other half will be taxed at the tax payer’s personal income tax rate for that year. Say you purchased a property for $400,000 in the year 2010. All your costs, legal fees and stamp duty might take that up to $440,000. Allowing for a claim of depreciation in the first two years of $10,000 per year, your cost base would come down to $420,000. When you then sell the property for $600,000, you show a capital gain of $180,000. Your tax is calculated on 50 per cent ($90,000) of the capital gain and if you’re in the top tax bracket, you’d be paying 45 per cent of that, or $40,500. If your top marginal tax rate is 37 per cent, you would pay $33,300. (This is the maximum amount, as you can index your costs to inflation for the two years.) The percentages do not include any Medicare levy or surcharge.

Note that depreciation only postpones your tax liability. It gives you an immediate cash flow benefit but also reduces the cost of the property on your books so that when you sell, your capital gain is higher. Depreciation is a cash flow tool not a method of tax avoidance.

The truth is I don’t worry too much about CGT regarding my passive portfolio because I claim the maximum depreciation (for the cash flow benefits) and I don’t sell. I leave the portfolio in place, generating income and capital growth. But I also have an active portfolio and in this portfolio, I’m a trader. I trade under various corporate names (with trusts) to allow me to distribute the income so I pay company tax which is 30 per cent.

Looking into a crystal ball for a moment, I see CGT reducing as Australia’s population continues to age and wants to realise its assets. There is already a provision to defer CGT on the sale of a business so people can reinvest in a similar business. If you have an investment portfolio for 15 years and during that time you turn 55, you can realise your assets, change asset classes and defer your CGT. For example, say you had 10 investment properties that had a capital gain in them of $1 million: you started building that portfolio 15 years ago, and you are now 60. If you want to realise that portfolio, you could invest the money in another asset class (perhaps in a managed fund that specialised in the property): you would not have to pay CGT at that time until the investments are finally realised.

It’s certainly worth thinking about CGT when you’re forming your long- and short-term financial goals. Discuss your objectives with your accountant; the trade-off between depreciation and capital gains; and how you will hold your investment structure (in your own name, your spouse’s name, a family trust or company). Also, it might a good idea to set up your own superannuation fund because if you retire early at 55, with a capital gains windfall you can transfer $500,000 to your super as a one-off, with tax concessions. As I say, sit down with your accountant.

>>> Coming Next: Manage your tax deductions

Please note: This is an extract from the Success From Scratch – it may not contain the exercises from the full version of the book/audio set, for full version please contact us or follow our blog for more.

Thank you,

The team@Custodian